India, long in the tooth when it comes to co-opting tech to persuade the public, has become a global hot spot when it comes to how AI is being used, and abused, in political discourse, and specifically the democratic process. Tech companies, who built the tools in the first place, are making trips to the country to push solutions.

Earlier this year, Andy Parsons, a senior director at Adobe who oversees its involvement in the cross-industry Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI), stepped into the whirlpool when he made a trip to India to visit with media and tech organizations in the country to promote tools that can be integrated into content workflows to identify and flag AI content.

“Instead of detecting what’s fake or manipulated, we as a society, and this is an international concern, should start to declare authenticity, meaning saying if something is generated by AI that should be known to consumers,” he said in an interview.

Parsons added that some Indian companies — currently not part of a Munich AI election safety accord signed by OpenAI, Adobe, Google and Amazon in February — intended to construct a similar alliance in the country.

“Legislation is a very tricky thing. To assume that the government will legislate correctly and rapidly enough in any jurisdiction is something hard to rely on. It’s better for the government to take a very steady approach and take its time,” he said.

Detection tools are famously inconsistent, but they are a start in fixing some of the problems, or so the argument goes.

“The concept is already well understood,” he said during his Delhi trip. “I’m helping raise awareness that the tools are also ready. It’s not just an idea. This is something that’s already deployed.”

Andy Parsons, senior director at Adobe. Image Credits: Adobe

The CAI — which promotes royalty-free, open standards for identifying if digital content was generated by a machine or a human — predates the current hype around generative AI: It was founded in 2019 and now has 2,500 members, including Microsoft, Meta, and Google, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and the BBC.

Just as there is an industry growing around the business of leveraging AI to create media, there is a smaller one being created to try to course-correct some of the more nefarious applications of that.

So in February 2021, Adobe went one step further into building one of those standards itself and co-founded the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) with ARM, BBC, Intel, Microsoft and Truepic. The coalition aims to develop an open standard, which taps the metadata of images, videos, text and other media to highlight their provenance and tell people about the file’s origins, the location and time of its generation, and whether it was altered before it reached the user. The CAI works with C2PA to promote the standard and make it available to the masses.

Now it is actively engaging with governments like India’s to widen the adoption of that standard to highlight the provenance of AI content and participate with authorities in developing guidelines for AI’s advancement.

Adobe has nothing but also everything to lose by playing an active role in this game. It’s not — yet — acquiring or building large language models (LLMs) of its own, but as the home of apps like Photoshop and Lightroom, it’s the market leader in tools for the creative community, and so not only is it building new products like Firefly to generate AI content natively, but it is also infusing legacy products with AI. If the market develops as some believe it will, AI will be a must-have in the mix if Adobe wants to stay on top. If regulators (or common sense) have their way, Adobe’s future may well be contingent on how successful it is in making sure what it sells does not contribute to the mess.

The bigger picture in India in any case is indeed a mess.

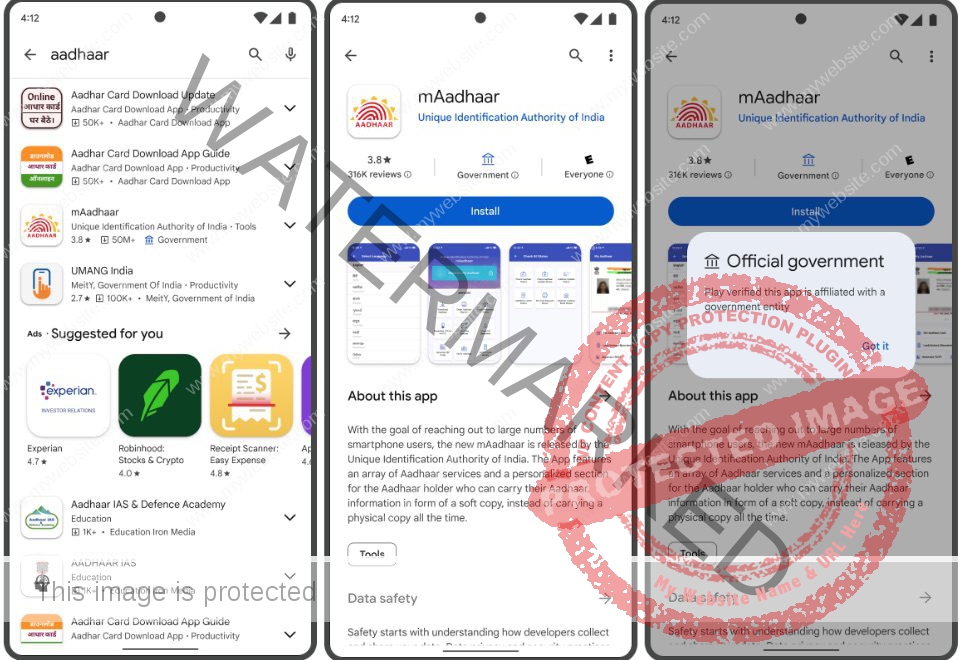

Google focused on India as a test bed for how it will bar use of its generative AI tool Gemini when it comes to election content; parties are weaponizing AI to create memes with likenesses of opponents; Meta has set up a deepfake “helpline” for WhatsApp, such is the popularity of the messaging platform in spreading AI-powered missives; and at a time when countries are sounding increasingly alarmed about AI safety and what they have to do to ensure it, we’ll have to see what the impact will be of India’s government deciding in March to relax rules on how new AI models are built, tested and deployed. It’s certainly meant to spur more AI activity, at any rate.

Using its open standard, the C2PA has developed a digital nutrition label for content called Content Credentials. The CAI members are working to deploy the digital watermark on their content to let users know its origin and whether it is AI-generated. Adobe has Content Credentials across its creative tools, including Photoshop and Lightroom. It also automatically attaches to AI content generated by Adobe’s AI model Firefly. Last year, Leica launched its camera with Content Credentials built in, and Microsoft added Content Credentials to all AI-generated images created using Bing Image Creator.

Image Credits: Content Credentials

Parsons told TechCrunch the CAI is talking with global governments on two areas: one is to help promote the standard as an international standard, and the other is to adopt it.

“In an election year, it’s especially critical for candidates, parties, incumbent offices and administrations who release material to the media and to the public all the time to make sure that it is knowable that if something is released from PM [Narendra] Modi’s office, it is actually from PM Modi’s office. There have been many incidents where that’s not the case. So, understanding that something is truly authentic for consumers, fact-checkers, platforms and intermediaries is very important,” he said.

India’s large population, vast language and demographic diversity make it challenging to curb misinformation, he added, a vote in favor of simple labels to cut through that.

“That’s a little ‘CR’ … it’s two western letters like most Adobe tools, but this indicates there’s more context to be shown,” he said.

Controversy continues to surround what the real point might be behind tech companies supporting any kind of AI safety measure: Is it really about existential concern, or just having a seat at the table to give the impression of existential concern, all the while making sure their interests get safeguarded in the process of rule making?

“It’s generally not controversial with the companies who are involved, and all the companies who signed the recent Munich accord, including Adobe, who came together, dropped competitive pressures because these ideas are something that we all need to do,” he said in defense of the work.